Review of Brakke's Gnosticism Lectures

I've decided to learn more about religion because (1) one of my biggest objection to theism is basically the theodicy issue, but there many proposed theodicies which I am not familiar with (though even without that, it is hard to see why it would make sense to take ancient scriptures so seriously...) and (2) if there is a true religion, that is the single most important fact about the world so on the off-chance that there is one it is worth studying religion in some detail.

I picked up these lectures about gnosticism because I had thought that gnosticism explained the existence of evil by saying there were two equally powerful gods, one good and one evil. I think this would be more logical than free will or original sin based theodicies (I am more sympathetic to divine command theory). I also was interested gnosticism seems like a cool form of esoterica and I really like the simulation theory which is reputed to be similar to gnosticism.

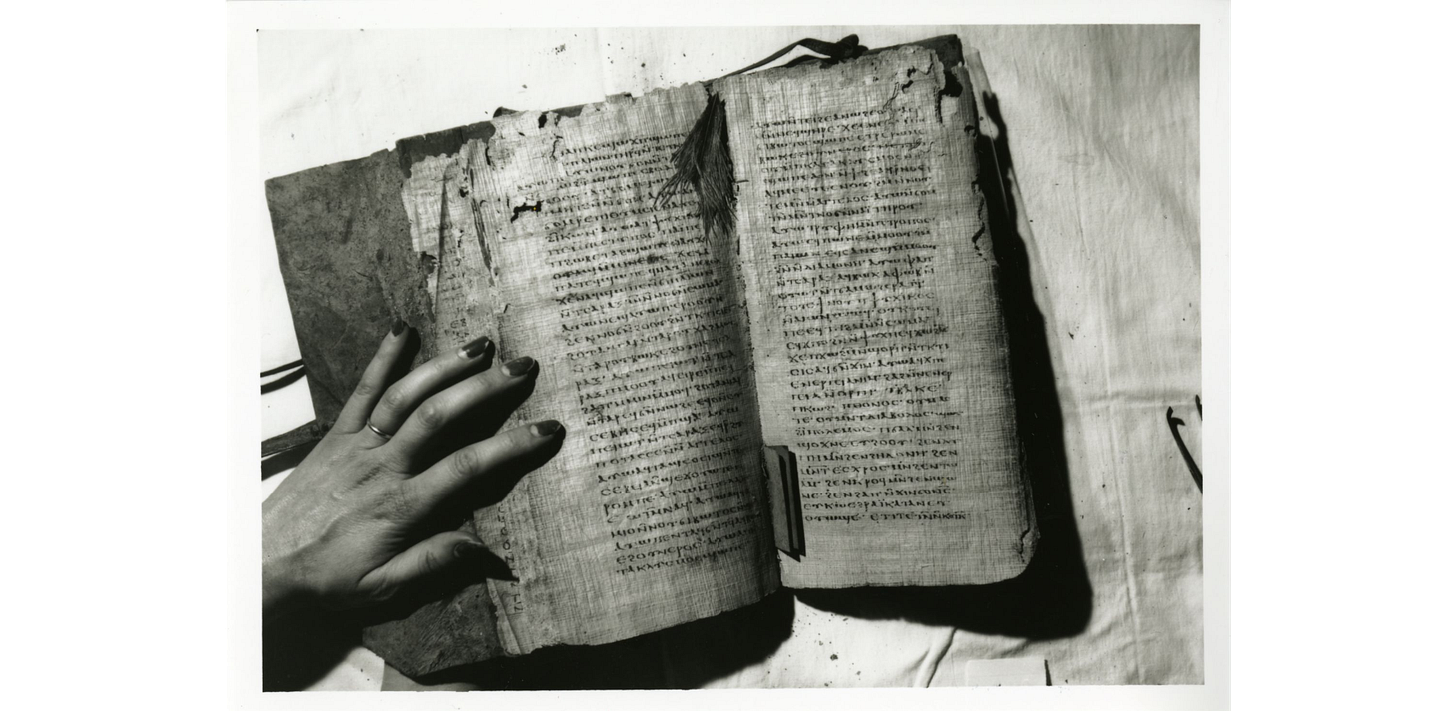

The gnostic literature discussed in this course was mostly discovered in a buried jar near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. The manuscripts were copied in the 3rd and 4th centuries. If I understand correctly, the writings were originally composed in Greek, but the versions found at Nag Hammadi had been translated into Coptic. Coptic is actually a late form of Ancient Egyptian and remains the liturgical language of Egyptian Christians.

Apparently the echt gnostics were not actually dualists in the sense of believing in equally powerful good and evil gods. Rather, they thought that the god of this world was created accidentally by higher gods (one of whom was called "the Barbelo"--apparently the origin of this name is now lost). The higher gods then created humans, but the evil god of this world ("Ialdabaoth") had some role in making humans worse. The gnostic myth, as it appears in the Apocryphon of John, is very complicated, as Brakke says many times. It is also not correct to call the group that tried to correct for Ialdabaoth's actions many separate gods--apparently they are aeons or emanations of the highest level of god (I guess this is a bit like penumbras and emanations). I think I might read the Apocryphon of John.

The discussion of the other works was less interesting to me than the Apocryphon of John. The Gospels of Thomas and Judas did not really hold my attention at all.

Manicheanism is apparently actually closer to what I had previously thought gnosticism was, in that it is really a religion about a good god and an evil god. I guess they got this from Zoroastrianism. But Manicheans seems to have had a kind of pathological obsession with purity and hostility to the world. Which makes sense--they thought the world was created by an evil god.

Apparently Origen had some beliefs similar to gnostic beliefs and was also a universalist. This seems like a much more coherent theology than most I have heard of (for problem of evil reasons). I may want to read Origen.

I didn't quite understand whether Brakke was saying that various movements similar to gnosticism: Cathars, Merkabah mysticism, the writings of Origen, etc., were actually influenced by gnostics or were just motivated by similar concerns. The desire to explain evil and get direct access to God are probably both recurring. I appreciated Brakke's awareness that two things being similar to each other does not mean that the first one caused the second one. Many historians struggle to grasp this point.

A friend told me that he thinks that the Catholic reading of the New Testament according to which people survive bodily death because they have incorporeal souls is incorrect. Rather, he says, the New Testament says that people's bodies will be revived before judgement. If he is right, then it seems like the gnostics may have had a role in introducing this distortion, because they hated everything corporeal. On the other hand, Platonism may be the common cause of gnostic and Catholic belief in an immaterial soul.

In Greek, gnosis means direct personal acquaintance, in this case with God. Brakke seems to be a proponent of gnosis in this sense and he kind of obliquely encourages listeners to use gnostic texts for spiritual purposes. If I was a Christian, I would probably find that to be subversive, but it makes for a more engaging teacher on this subject.